Who’s there?: The rise of multienterprise business networks

Not everything about business is technology, but every business has to leverage technology everywhere

Over the last few years, executives discussed redesigning their businesses for the safe, secure and accurate flow of actionable data with as little human involvement and oversight as possible, a change Google describes as removing the “human toil” from economic activity. Business leaders called this process optimization, a process often resisted by employees which in turn slows an organization’s digital efforts. Organizations big and small have been forced to embrace a cloud- and digital-first posture to maintain business continuity and participate in everyday economic activity. In short, these efforts are being done to maintain relevance. As a result, nontechnology-savvy executives and employees will exit the workforce exponentially over the next five years.

In this transformative period, future managers train now at new entry-level IT jobs, even as IT services vendors and other players in the technology ecosystem complain about a shortage of STEM talent in the hiring markets. The talent that does come on in new roles spread across a digitally savvy enterprise understands application interfaces, which align human interaction with technology and data platforms. By entering the business in this capacity, the incoming talent gains experience across the various elements of the business operation that executive managers require while also ensuring they are fully digitally versed for the Business of One.

Adding further complexity has been the disaggregation of business functions or value among different business entities. In technology we see this as the IP-centric elements of a business being split away from the labor, or task-centric functions. Looking at semiconductors, for example, some on Wall Street are calling for Intel to be split between the IP-laden aspect of chip design and the capital-intensive aspect of fabrication plants capable of manufacturing those designs reliably at scale. They are two businesses with entirely different rhythms and economic drivers, yet neither can thrive without the other.

The work-around to this business disaggregation taking place is to establish a network of businesses with complementary value propositions. This network is increasingly being called the multienterprise business network (MEBN). Many technology-centric firms describe this as their platform. But platforms are a stage on which something is performed, and that performance is the outcome enabled by multiple different parties. As such, viewing MEBNs from solely a technology-centric view can miss the point entirely.

As the Business of One evolves, legacy technology vendors selling on technical merits, or speeds and feeds, and selling just to IT face tremendous market pressures to pivot to selling business outcomes. Today’s reality requires understanding customers’ busines objectives and speaking directly to business decision makers.

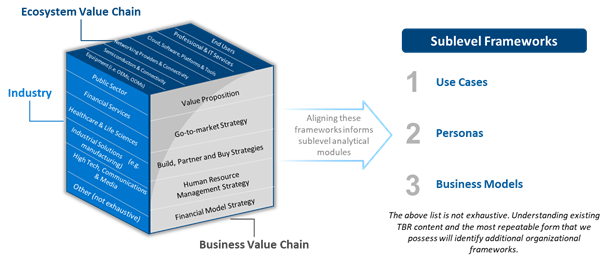

For Technology Business Research’s (TBR) Digital Practice, this necessitates taking our core value proposition of vendor-centric business analysis of technology companies across a standard technology business value chain and combining it with additional considerations about industries and the operating best practices of business ecosystems that tie back to the specific use case and the personas integral to that use case. After having established those core frameworks, the analysis then ties back to time horizon and MEBN participant. In short, what is in it for the MEBN participant at what stage (commonly referred to as Horizon 1, 2 and 3 in today’s frameworks) in the MEBN product road map.

To illustrate the intent here, consider the creation of an MEBN for the utilization, storage and maintenance of autonomous vehicles. Having autonomous vehicles moving about a defined geography would clearly be the Horizon 3 aspiration, which is nowhere near commercial reality today.

Horizon 1 would be delivering an immediate level of business value creation to entice the participants necessary for that Horizon 3 aspiration. For example, gas stations, mechanics and parking garages, at a minimum, will need to be recruited into the MEBN for autonomous vehicles. Later, additional services for the auto owner could be added such as online ordering with brick-and-mortar pickup across various nontech-centric small businesses providing localized services. Creating a buyer network in Horizon 1 for today’s cars and owners has to provide sufficient business value for enrolling participants.

The capital investment in the technology infrastructure likely must come from the Horizon 3 business benefactor and be viewed as a long-term investment to facilitate the recruitment of the necessary member participants. In the end, those autonomous vehicles will need the fueling, maintenance and parking services to function and the adjacent human services of pickup and delivery to increase their utilization rates beyond a source of human transport. Yes, it requires a technology value chain as its backbone, but nontechnology participants are just as necessary to flesh it out into a thriving MEBN of buyers and sellers who may not even concern themselves with the technology underpinnings at all.

More colloquially, few singer-songwriters would have the capital necessary to build the technology assets for downloading music over the internet. But once Apple took a long view to their investment posture, it was able to build out a robust MEBN that profited many artists, disrupted traditional nontechnology businesses, and delivered value to many customers in the form of the iTunes platform, which itself has been disrupted by streaming services such as Spotify and Pandora.

TBR’s Digital Practice remit is to take its core value proposition of discrete company business model analysis and apply it to the MEBNs by isolating the different components through a series of frameworks. In doing this, we will then be able to assess the financial impact for the different member participants across the near-term, mid-term and long-term horizons.

Industries have different automation leverage points, enabling different personas; inexpensive tech makes possible a myriad use cases

Compute ubiquity has been well documented. The multimillion-dollar supercomputer performance of yesteryear is now contained in smartphones. The first IBM PC chip, the 8088, is now matched by CPUs the size of a grain of sand that cost $0.10 to produce. Historically, the heavily regulated industries of financial services and healthcare were early technology adopters, given the risk exposure of noncompliance with government regulation. As the cost of compute was brought down to incredibly inexpensive price points, compute expanded from those back-office functions into front offices. Today, we are at a point where, as on EY executive summed it up in analyst interaction when peppered with multiple questions: “We can do whatever you want; you just have to make up your minds.”

Making up our minds translates into codification of standard business results to digitize activity in a consistent way, and this sits at the heart of multiple game-changing technologies including AI, machine learning and blockchain. And these are horizontal technological capabilities that cascade through a variety of industries. Retail, once cost-conscious, was one of the later industries to adopt technology. Amazon, as we know, has disrupted this sector at the detriment of many high-profile brick-and-mortar brands of yesteryear.

TBR will use this construct to incubate standard coverage of markets, facilitating a way to bring analysis of that market to a vendor-centric view. TBR’s Digital Transformation research portfolio will serve as the vehicle to introduce these frameworks. The inaugural Digital Transformation Blockchain Market Landscape is set to publish in April 2021 and Digital Transformation IIoT Market Landscape will be published in June 2021. These reports will follow a semiannual publication cadence.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!