Business ecosystems must invest in massive supply chain pivots

COVID-19 supply chain impact

COVID-19 laid bare the underinvestment in contingency capabilities during the decades-long pursuit of cost optimization. In short, business leaders assumed a certain status quo in business continuity and did not leave sufficient capital tied up in unfinished inventory to provide necessary buffers in supply chain efficiency. Firms had over-rotated on optimization and perhaps assumed their trading partners were on par with them in terms of the technology “twinning” of their activities. COVID-19 exposed the need for agility, and when scale advantage only enabled top-tier firms to have the automated tool sets, working with the vital Tier 3 and Tier 4 suppliers resulted in the cascading pileups now in the news.

Future supply chains have to be embrace open contributions

Uneven technology enablement with supply chain participants certainly has created a network effect, but not the positive force multiplier discussed in third-wave economics papers. Supply chains, by definition, are a collection of ecosystem participants. For there to be a positive network effect, there has to be democratized access to technology innovations. Tier 3 and Tier 4 suppliers lack the funds and the skills to build digitally transformed supply chains on their own. In this sense all enterprises have to learn a lesson from the technology industry in terms of IP contributions to the ecosystem.

Ecosystems have to provide a common platform of nondifferentiable value-add to all participants —value-add in terms of stripping labor and labor mistakes from process flows, and nondifferentiable as it impacts neither ideation nor sales engagement. Open source is how technology has wrung cost of compute out of the model. This is how platform businesses achieve the network effect, as positively espoused in third-wave economics.

Supply chain has the attention of the boardroom

The value of the interconnected supply chain ecosystems has been gaining boardroom attention and, as EY notes, COVID-19 only accelerates the need. The pandemic was a blindside disruptor and, as enterprises get back up from the blindside hit, the focus shifts from the diminishing return of investing in supply chain for cost optimization and turns back to the double-digit revenue hits enterprises took due to pandemic-fueled disruptions. The board focus is now on gaming out what other events could have a similar impact on business resiliency that the pandemic has had.

Does the boardroom see value in ecosystems yet?

Boards generally are populated by mature executives well versed in the current ways of working. Ecosystem business models are not a legacy best practice with which TBR would expect many board members to be familiar. They are too new. The idea of taking huge sunk investment costs and donating them to a buyer/supplier consortium will likely be anathema to many boards, but, as technology has proven time and again, open-source communities accelerate innovation. Linux/Red Hat represents just one illustration of that value creation in technology.

Advisory firms have permission to play to educate boards on ecosystem business model best practices

TBR hears a constant refrain in its discussions with services firms that people and process are the constraints and not the technology itself. This rings true with large enterprises but not necessarily with the small businesses comprising many of the Tier 3 and Tier 4 suppliers in enterprise supply chains. Outlining the value of a resilient supply chain will be an easy boardroom sell based on the current pandemic-related constraints being felt throughout the global economy. Convincing the board to contribute sunk IP investments to a consortium will be a harder sell. If any services entities can convince the boards of this efficacy, it will be the tax and audit advisory partners who have been providing business guidance to enterprises for centuries.

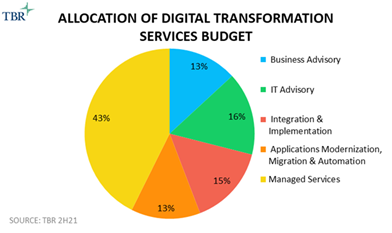

TBR’s recently published November 2021 Digital Transformation: Voice of the Customer Research bears out these notions. Based on survey data, respondents allocate 13% of their digital transformation services budget to business advisory services, another 16% to IT advisory services and an impressive 43% for managed services. TBR believes these managed services will more frequently flow from the advisory-led firms rather than the technology-led firms given the advisory firms’ advantage in knowing the business rules and business risks to digitization more than how to get the technology plumbing to work seamlessly.

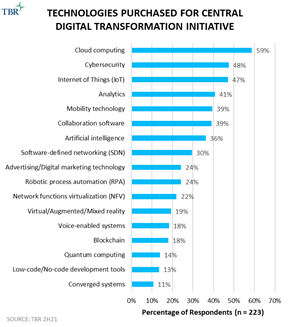

From a straight technology perspective, firms invest in cloud computing, cybersecurity, IoT and analytics for digital transformation. Cloud localizes the activity where the firm wants it, cyber mitigates risk, IoT allows for more workflow automation, and analytics tells the business leaders what is important from the frictionless business flows. Cloud similarly was brought to the fore during the pandemic given the need to accommodate remote workers and reduce the amount of on-premises IT equipment requiring on-site staff.

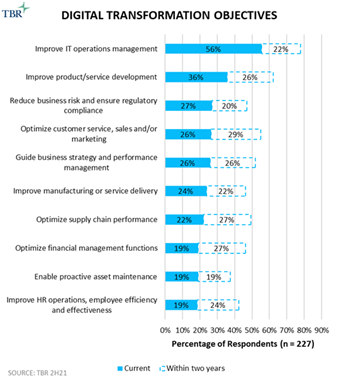

Of course, all of these statements hinge on having IT platform plumbing built correctly and then transforming the business workflows that sit atop the IT platform. Figure 3 highlights the need for this gradual rollout strategy. Right now, improving IT operations management dominates the list of respondents’ digital transformation objectives. In two years, however, there will be a string of different business workflows on the customer docket. Workflows are automating business processes that often engage with other corporate entities and customers. This is where the deep knowledge of business rules and business risks come into play, and where tax and audit firms have clear market distinction.

Technology-led firms, hyperscale cloud companies and equipment manufacturers will certainly all play roles in moving industries further along the path of digitization. But just as business is turning to ecosystems, so too must the technology-based firms move to ecosystem offers where advisory-led firms will increasingly take the leadership role to advise boards in formulating business risk and resiliency policies that drag the tech stack participants along as the derived decision from the C-Suite aspirations.

Supply chain is the current example where tech innovations, business rules and employee training will give businesses competitive advantage providedthose ecosystems extend the IP value to the Tier 3 and Tier 4 suppliers. Like a chain only being as strong as the weakest link, ecosystem networks are only as strong as the weakest participant.

The statement stands for all business ecosystems. Other aspects of the business value chain come to the fore as different events trigger different reactions and technological choke points in need of modernization and remediation.